Interstate Access & Employment Growth:

Evidence from a Design-Based Instrument

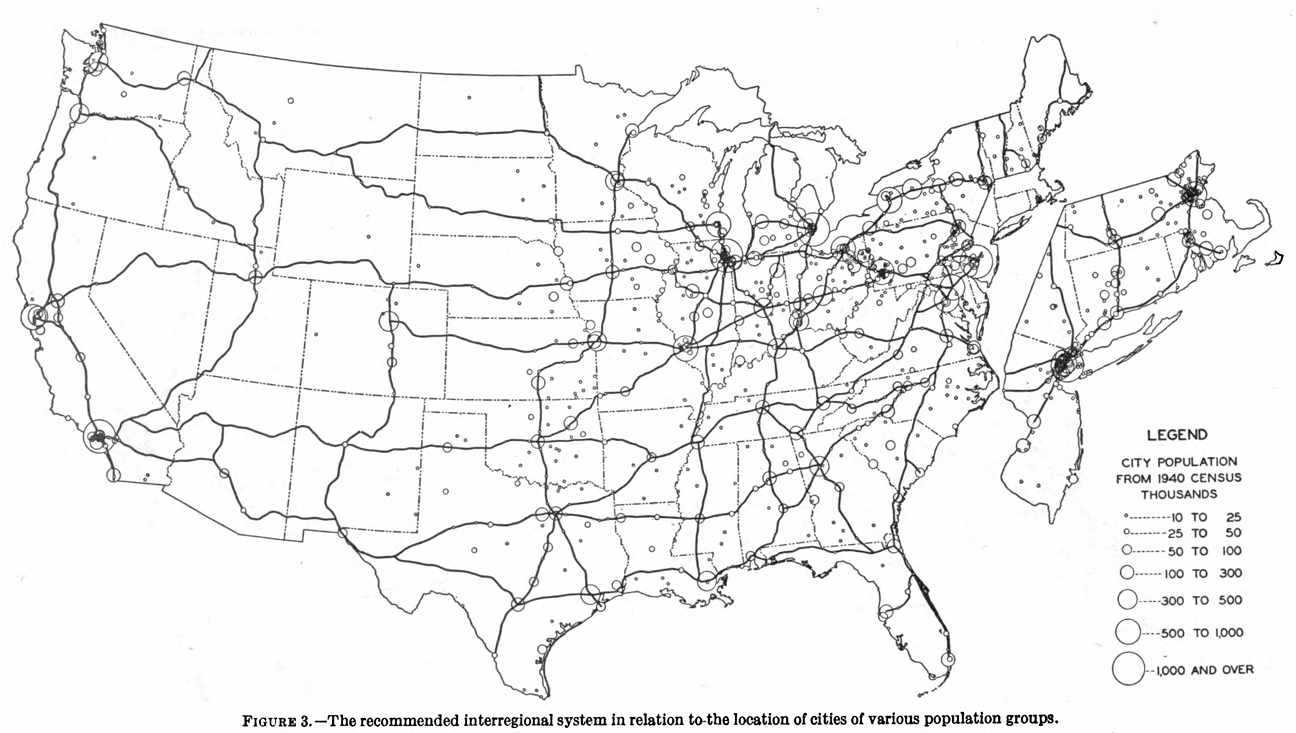

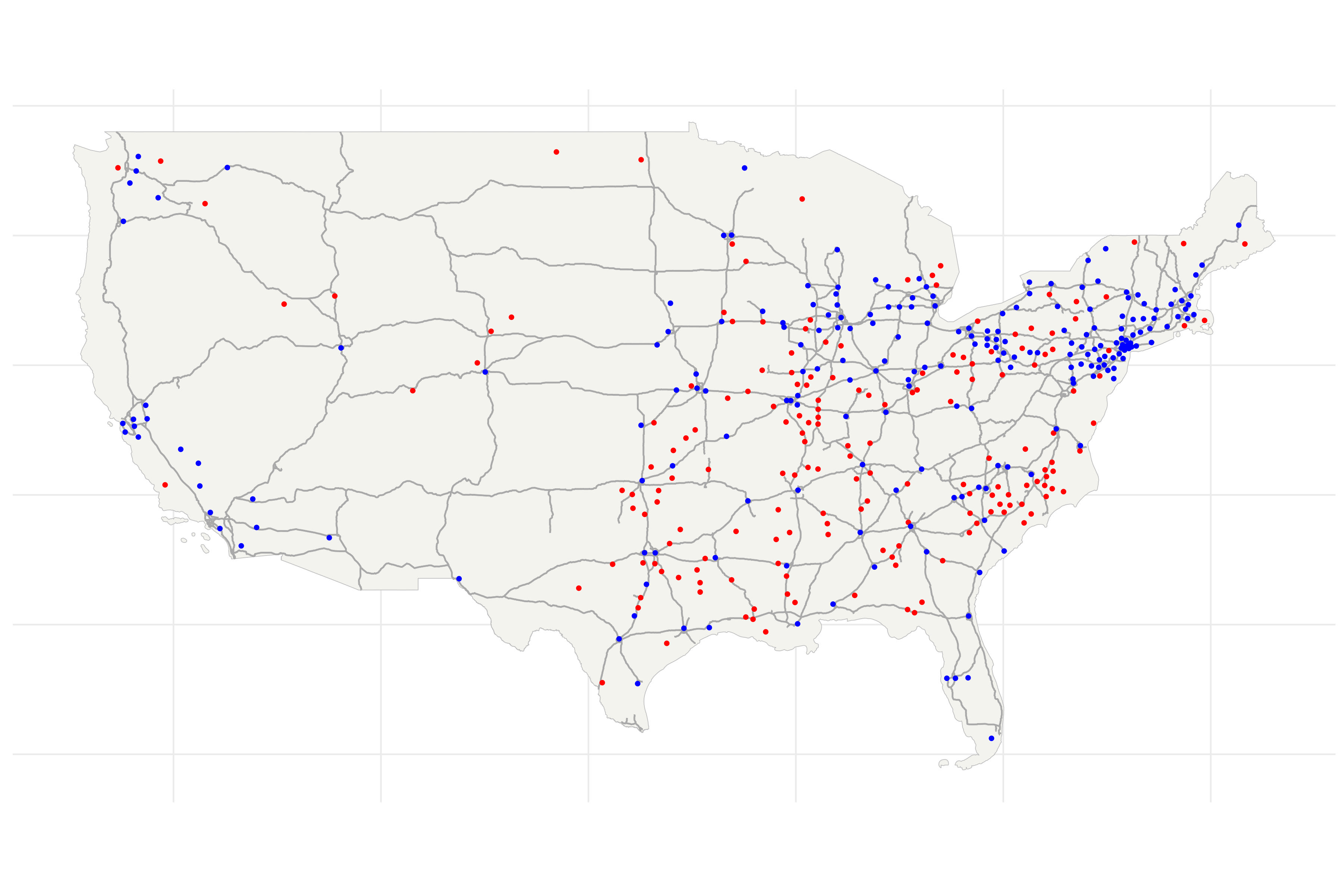

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 authorized the construction of the 41,000-mile Interstate system. Since then, employment has become increasingly concentrated in counties linked to the network.

These highways, of course, were not placed at random - they were planned to connect large cities. Therefore, this employment growth could be driven by concurrent forces of urbanization, rather than by Interstate access itself.

I develop a new design-based instrumental variable using an overlooked planning quirk that shaped counties’ Interstate access. Leveraging this source of quasi-experimental variation, I estimate the causal effect of Interstate access on county employment growth.

I find that, among counties that as-good-as-randomly gained Interstate access, employment only increased where agriculture was initially important.

Courtesy of ExxonMobil Corporation

Courtesy of ExxonMobil Corporation

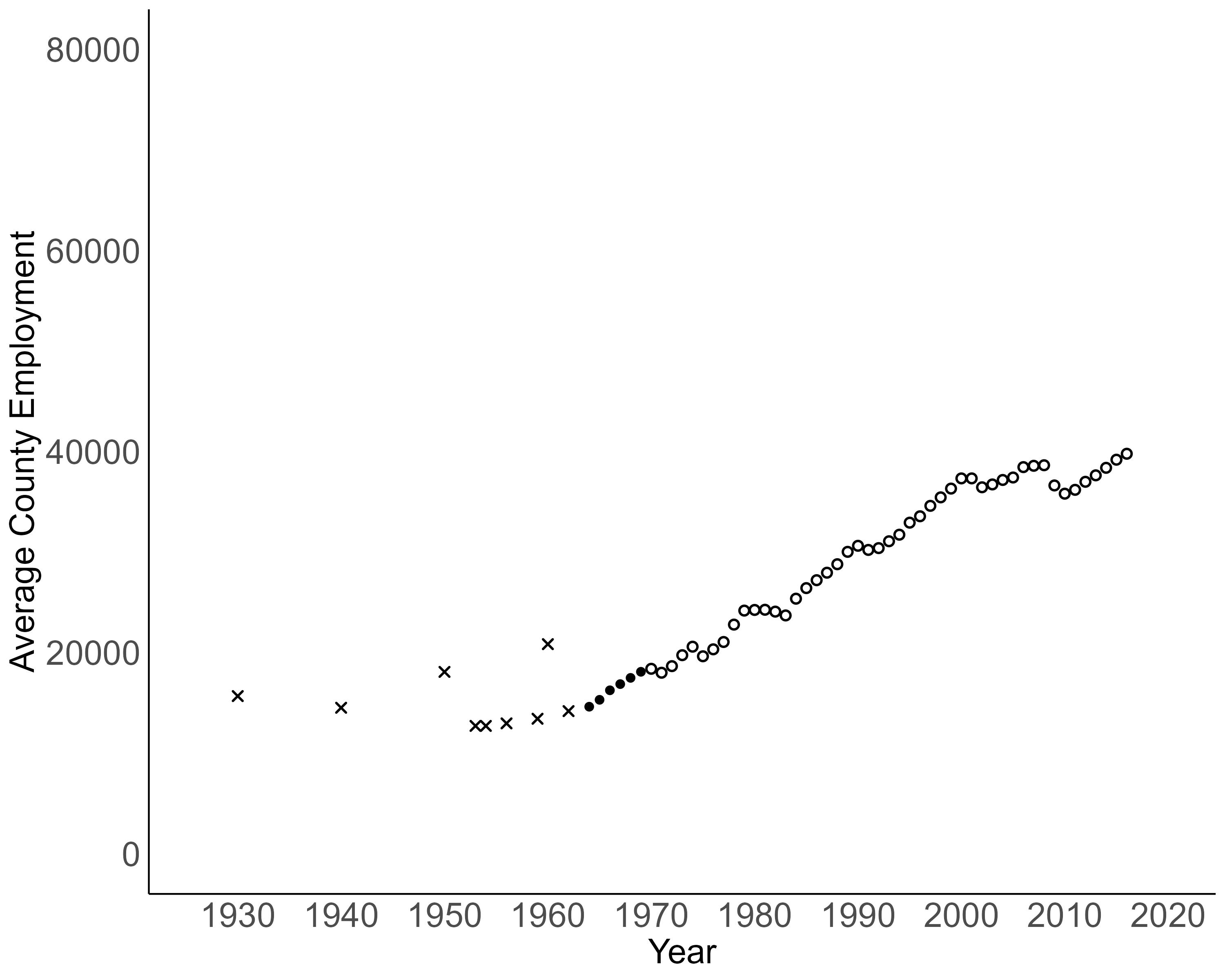

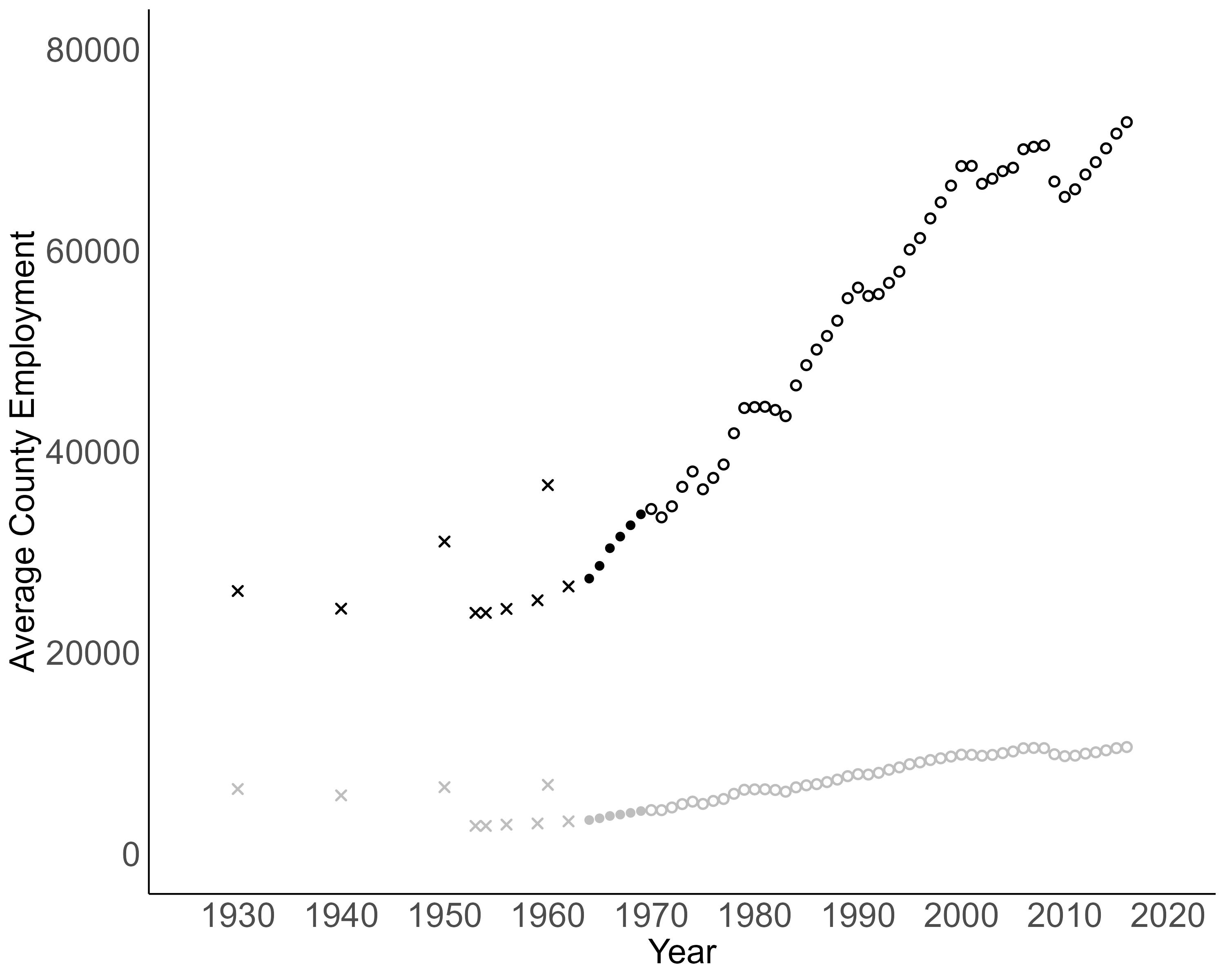

Raw Data & Employment Growth Regression

Raw Employment Growth Data

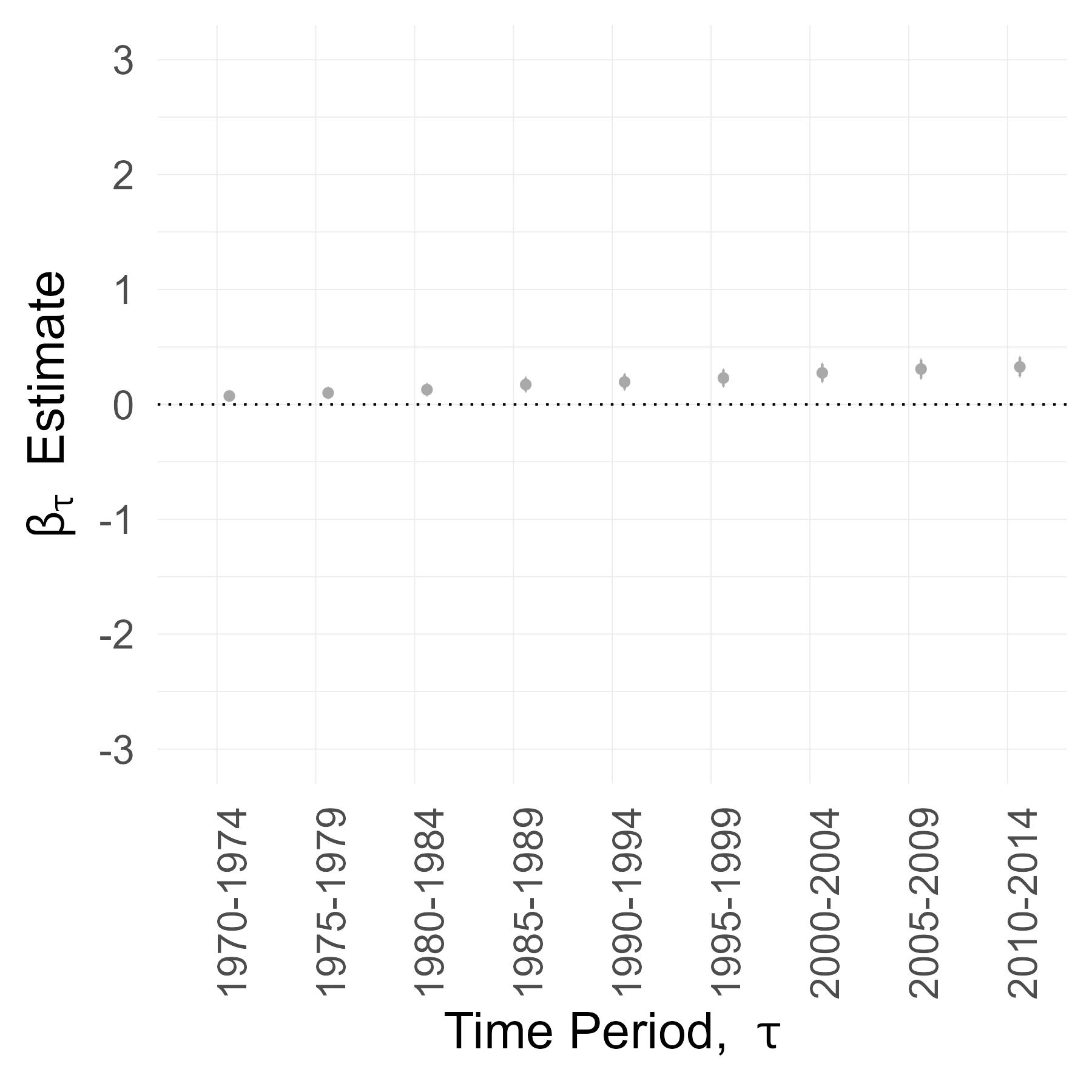

Baseline Employment Growth Regression Model

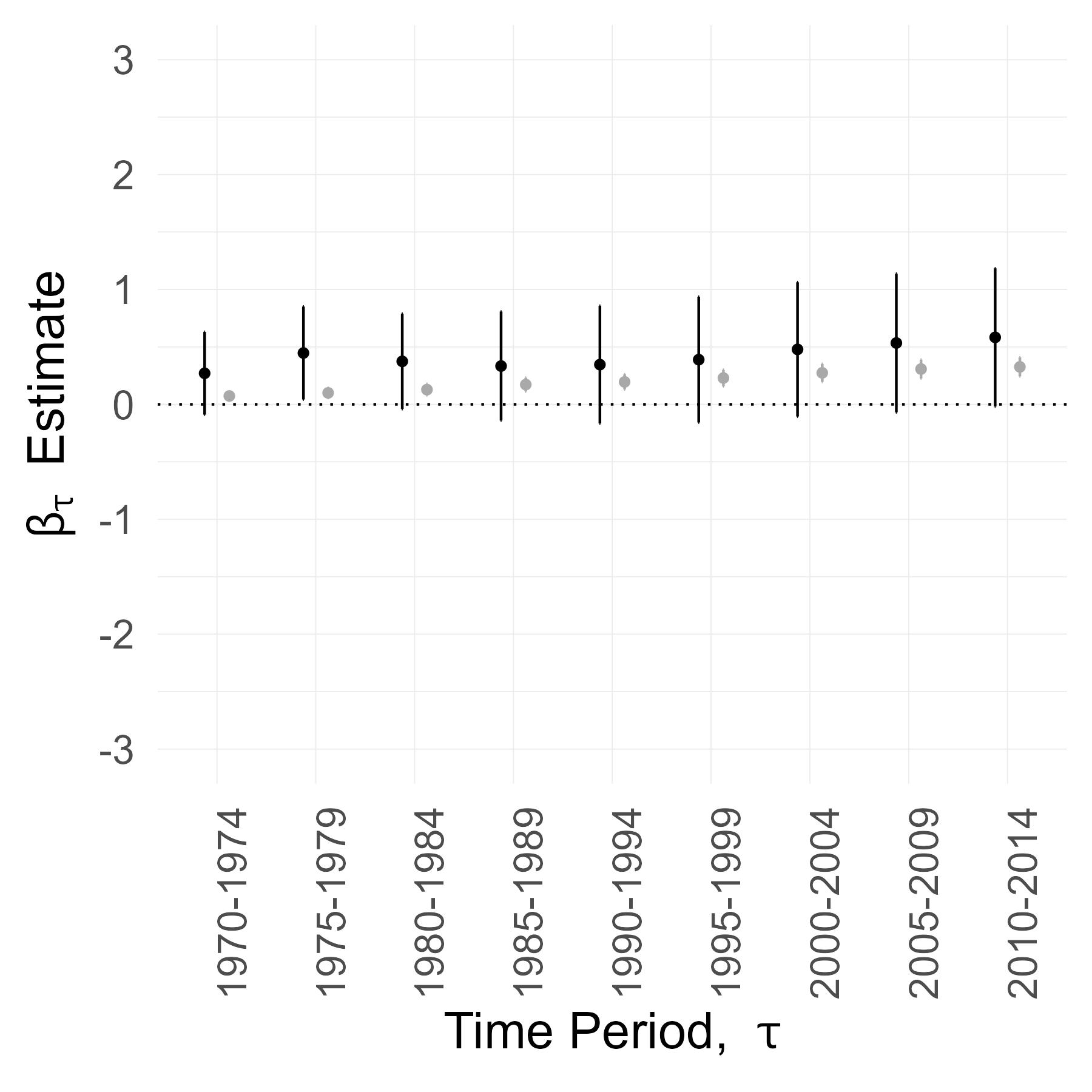

To flexibly capture dynamic effects while preserving statistical power, I group years into 5-year periods, \(\tau \in \{1970\text{-}1974,\,1975\text{-}1979,\,\dots,\,2010\text{-}2014\}\). For each period \(\tau\), I estimate the following specification, with counties indexed by \(c\):

\[ \log(Y_{c, t}) - \log(Y_{c,1953}) = \beta_{0,\tau} + \beta_{1,\tau}\,\text{Treatment}_{c} + X_{c}\gamma_{\tau} + \delta_{t} + \varepsilon_{c, t} \]

The dependent variable is the log change in employment in county \(c\) since 1953. The coefficient \(\beta_{1,\tau}\) measures the relationship between Interstate access and post-construction employment growth at period \(\tau\). The indicator \(\text{Treatment}_{c}\) equals one if county \(c\) was within 25km of an Interstate highway. The vector \(X_{c}\) includes baseline county characteristics measured prior to Interstate construction, and \(\delta_{t}\) denotes year fixed effects.

Constructing an Instrument to Control for Selection

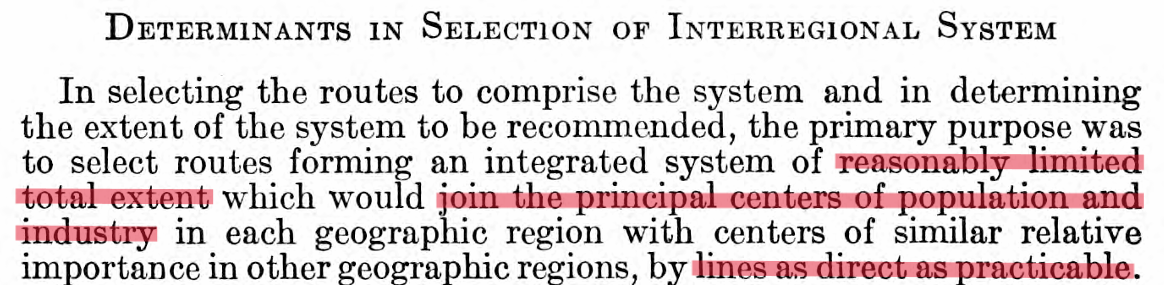

An exogenous planning shock?

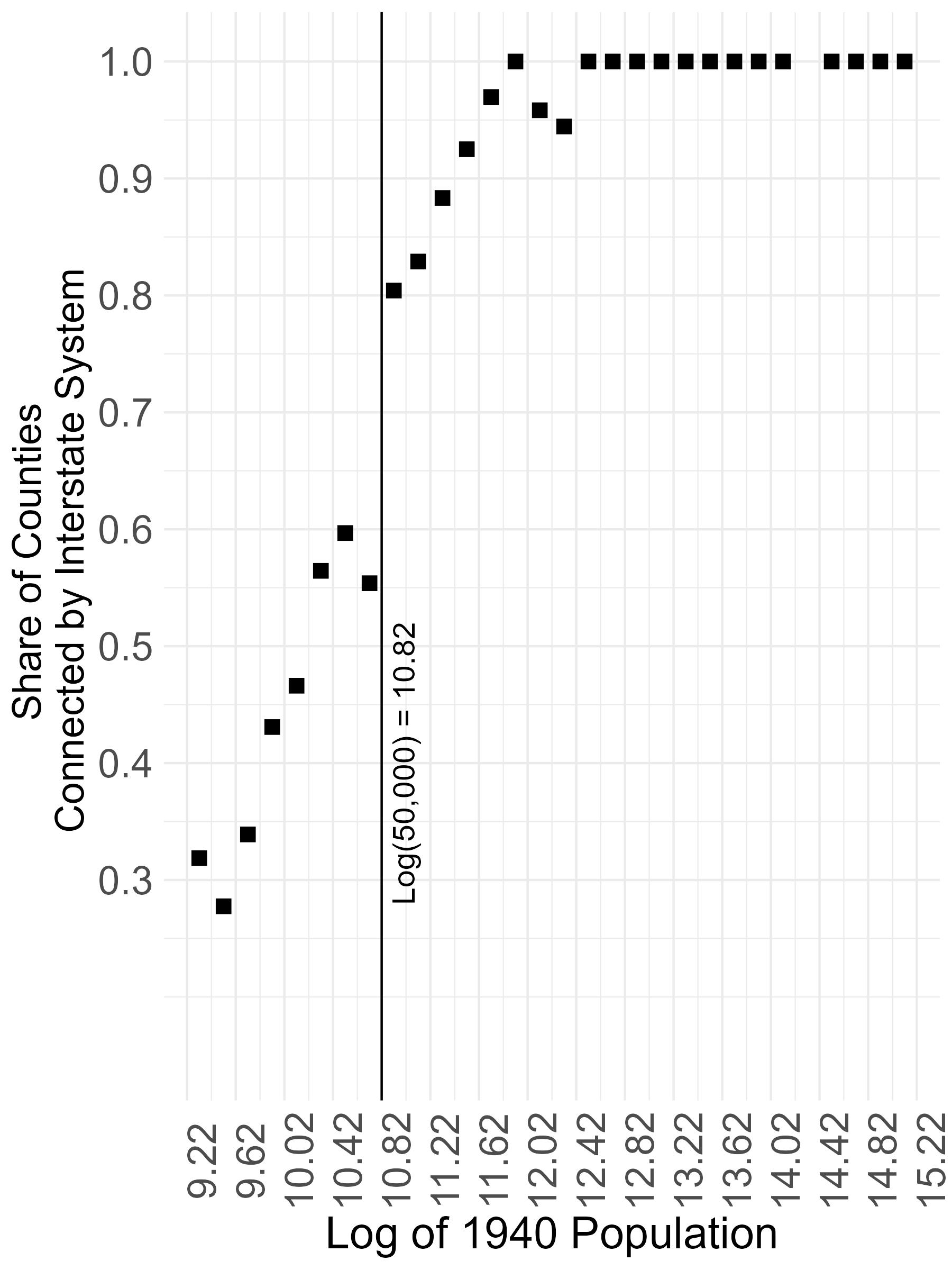

Testing for a Discontinuity

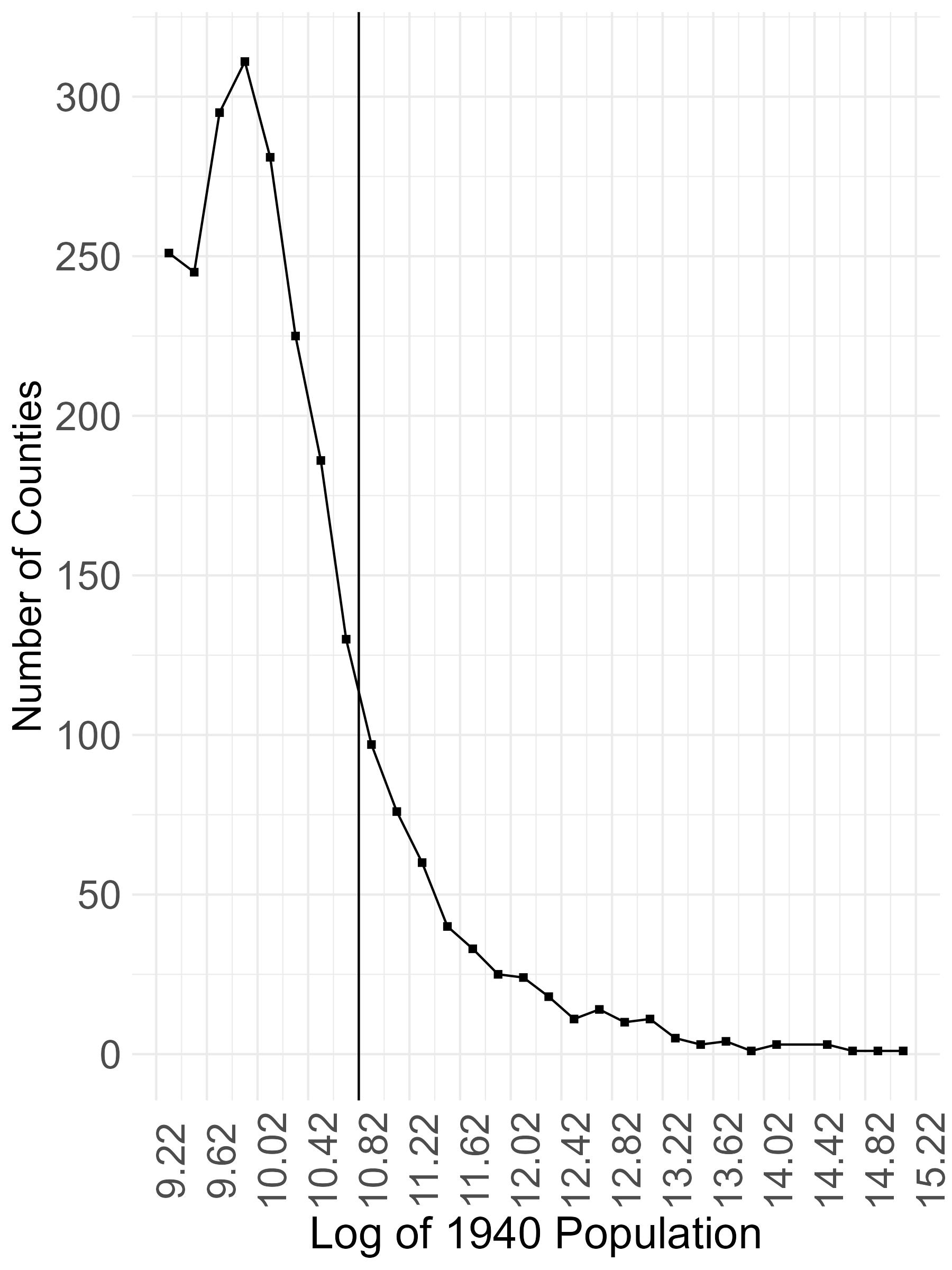

I overlay county boundaries from the 1940 Census with the Interstate system. Then, within bins of the log 1940 population, I compute the share of counties intersected by a highway. The probability of receiving an Interstate jumps by about 20 percentage points at the 50,000 population cutoff.

Additionally, other county characteristics and the density of counties remain smooth at this cutoff, which suggests that this is a natural experiment. Near the cutoff, there is a set of counties that shared similar potential outcomes, on average. However, for a random reason, only some of them gained Interstate access. This looks like a promising fuzzy RD design but, because it uses only counties near the cutoff, estimates are too underpowered to learn anything. So, what can we learn from this natural experiment?

💡 There is a lot of non-random exposure to this exogenous shock

For many counties, their distance to an Interstate depends partly on the exogenous inclusion of a near-cutoff population hubs to the Interstate network. In this spatial setting, the random inclusion of a county generates treatment variation in other counties that must be traversed to connect it to the network.

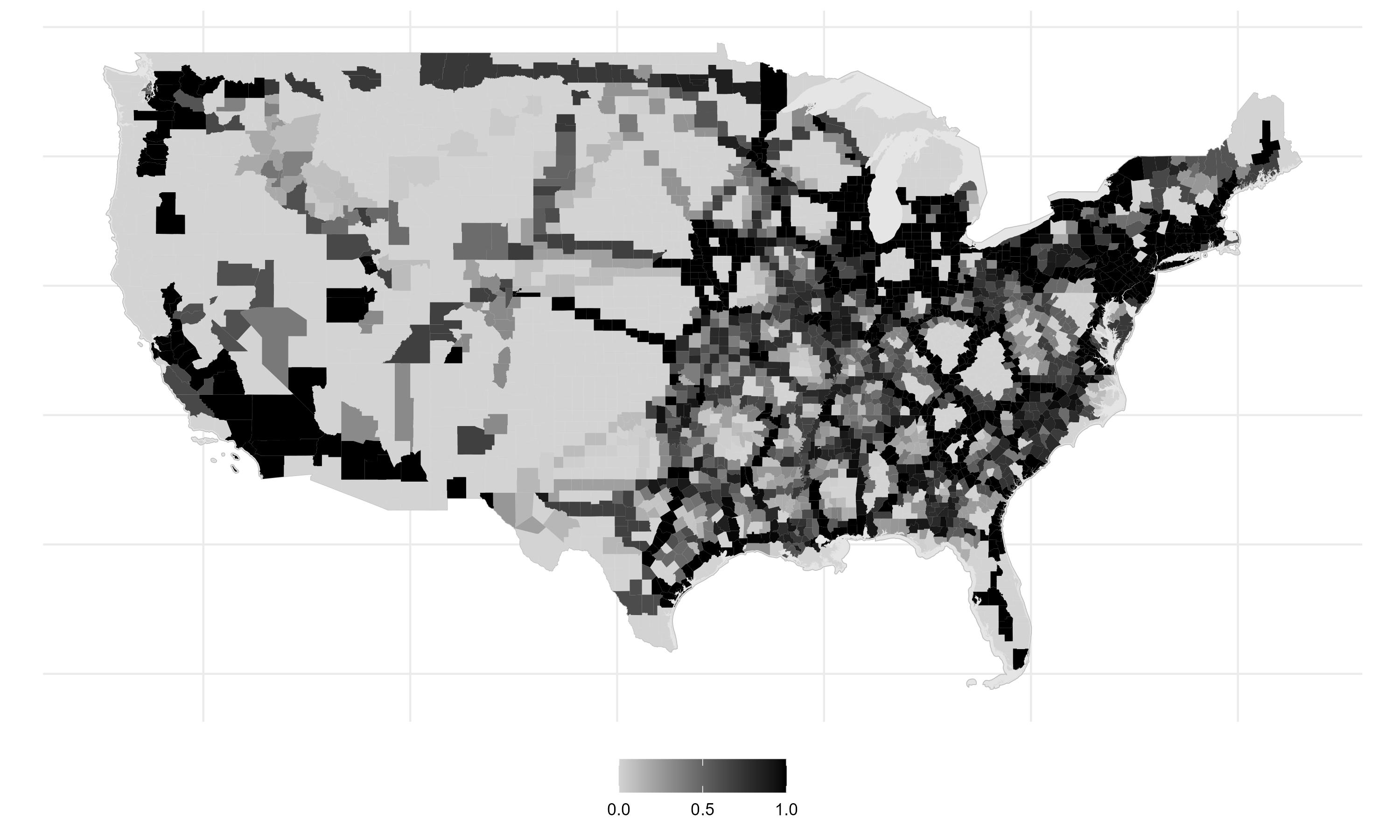

But exposure to this source of variation is itself non-random. The instrument I construct builds on this insight: it captures the induced treatment variation and, following Borusyak and Hull (2023), I apply their recentering procedure to isolate the random component.

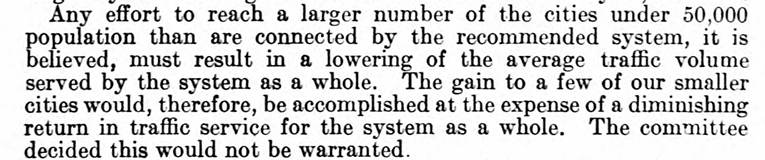

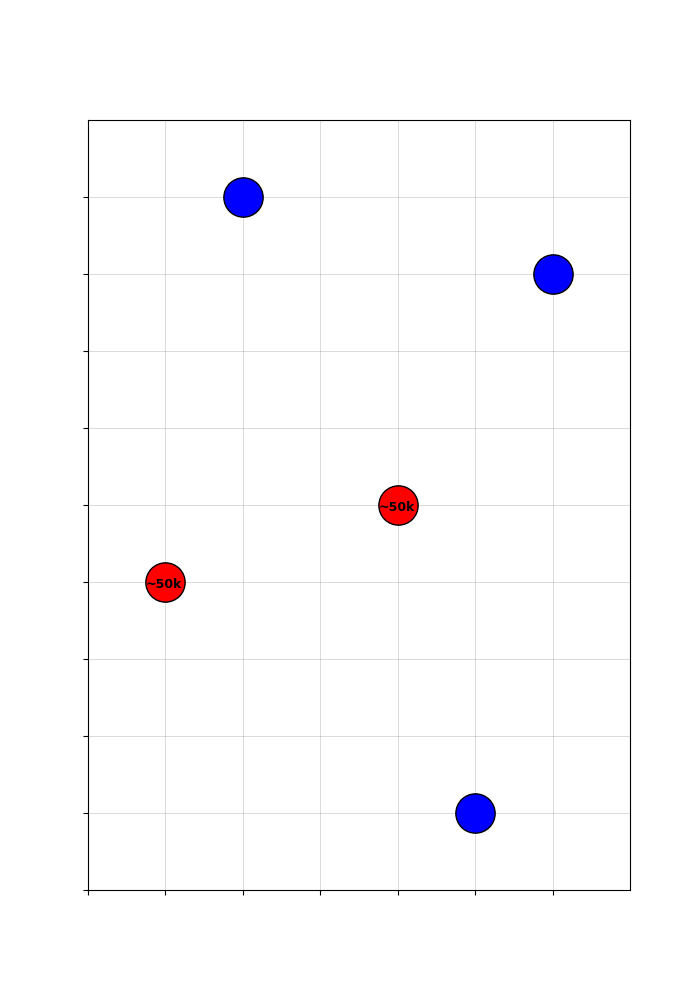

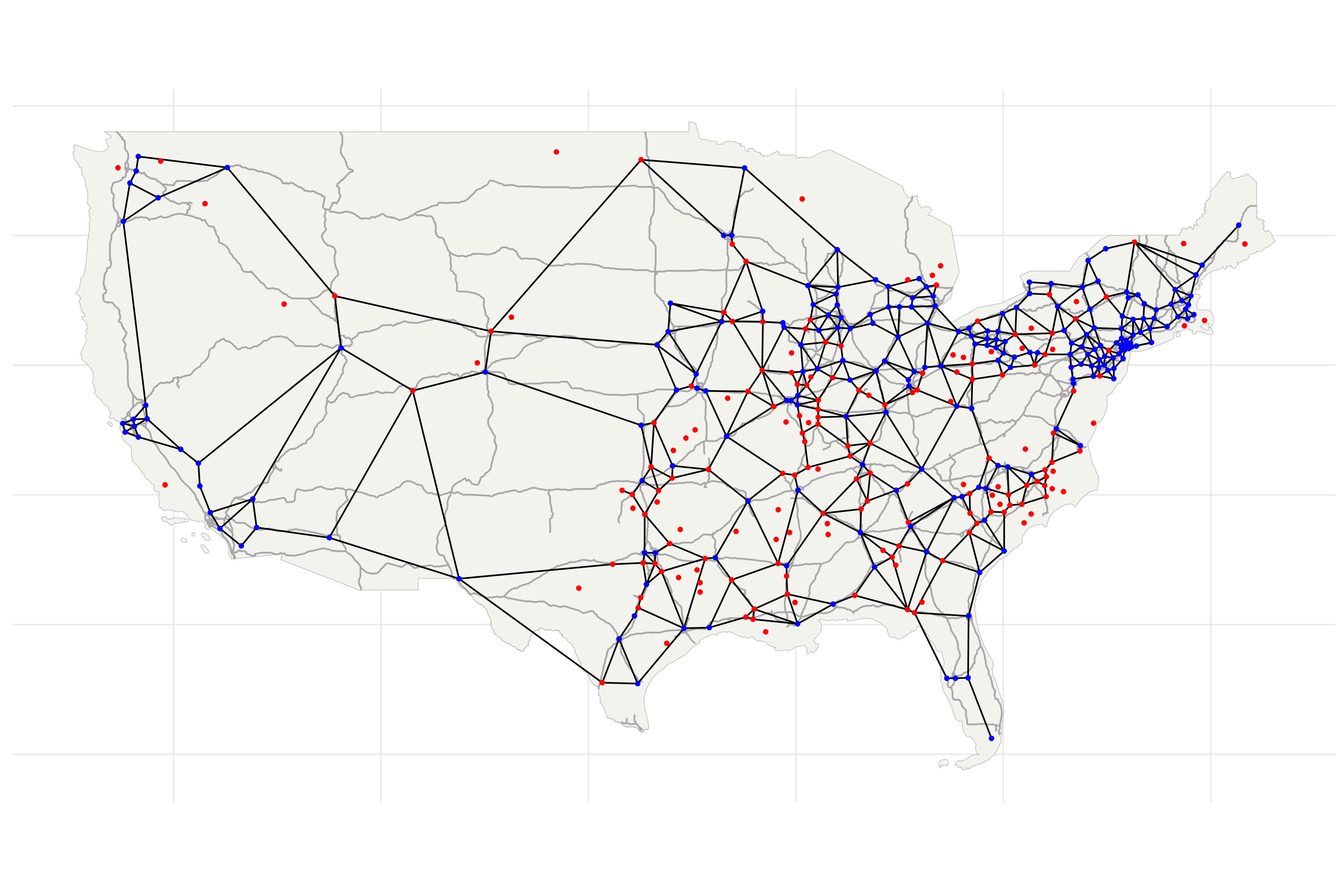

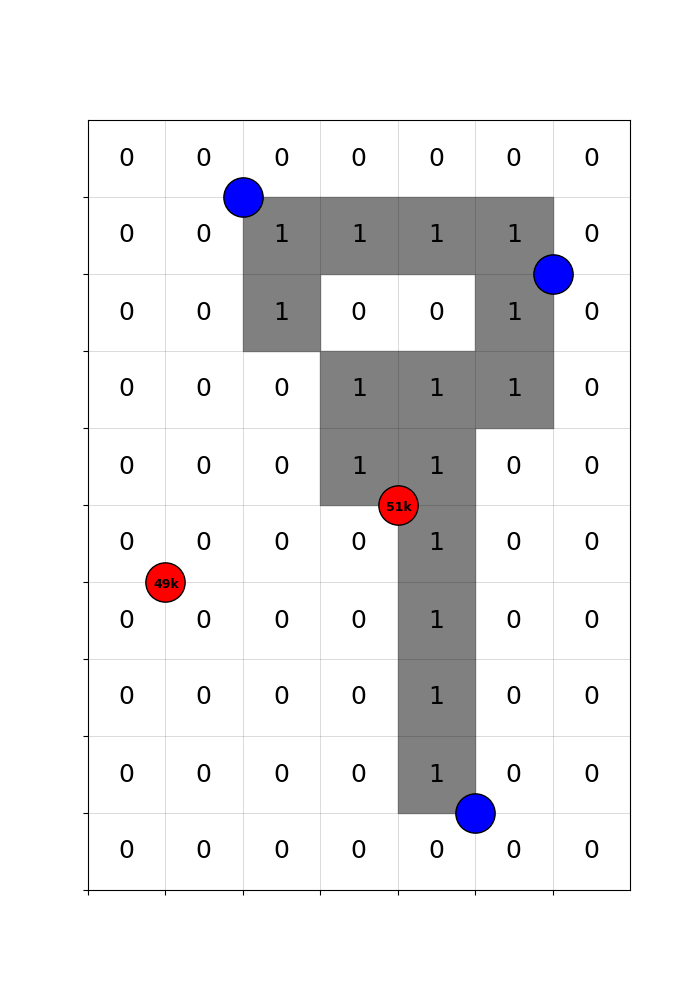

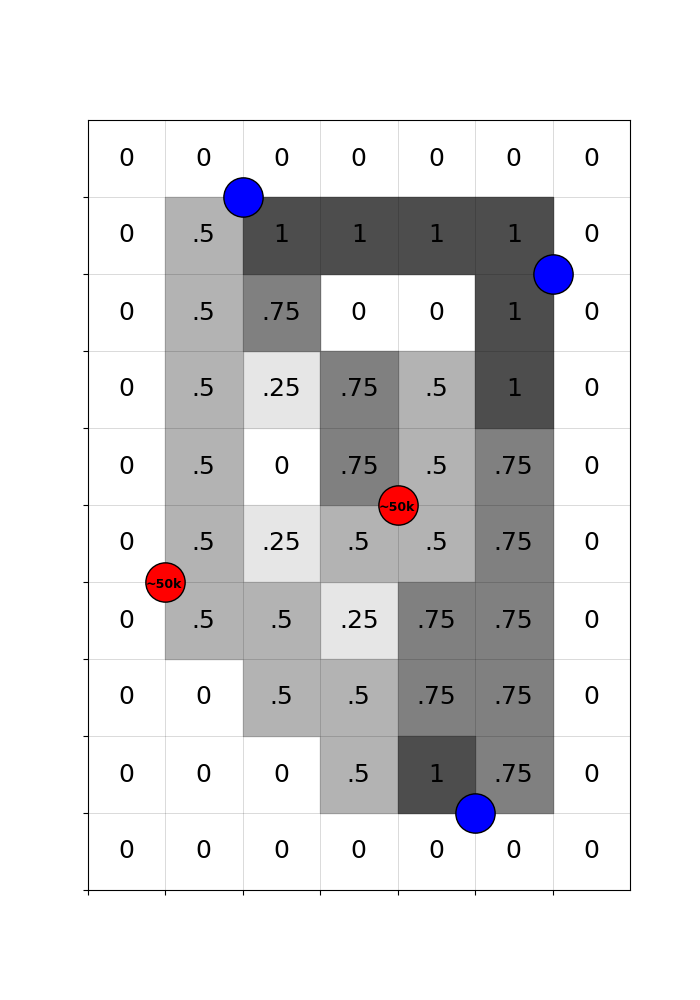

Stylized Example

A visualization of a stylized example will help.

🔧 Expected treatment captures non-random treatment variation

The treatment combines random variation (from the cutoff-driven coin flips) and non-random variation (from location-advantaged counties always selecting into the treatment group).

The goal, therefore, is to adjust for this non-random selection and recover the random treatment variation generated by the cutoff rule.

To this end, non-random treatment variation is summarized by the expected treatment across networks that could have been built, given the possible connection status of the coin-flip red hubs.

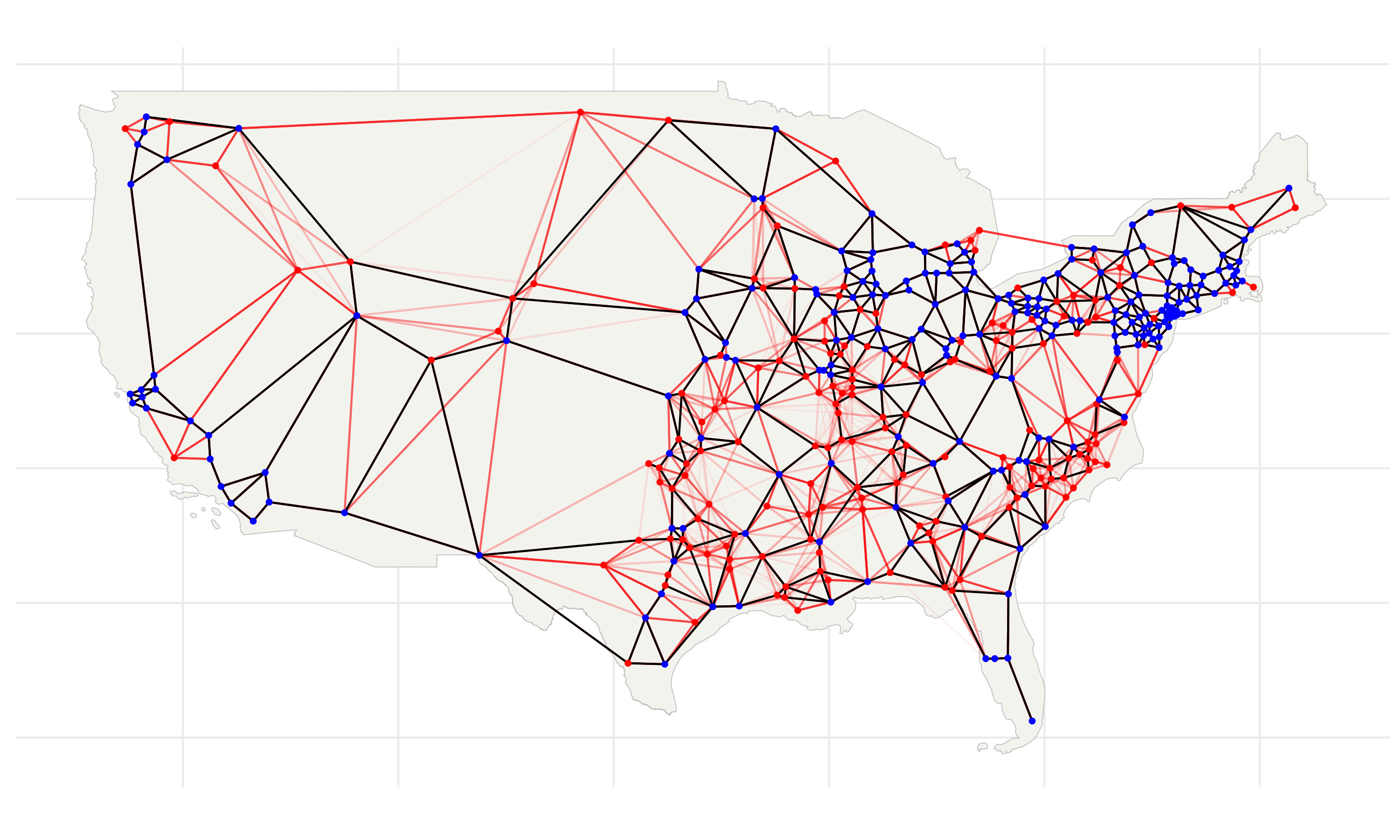

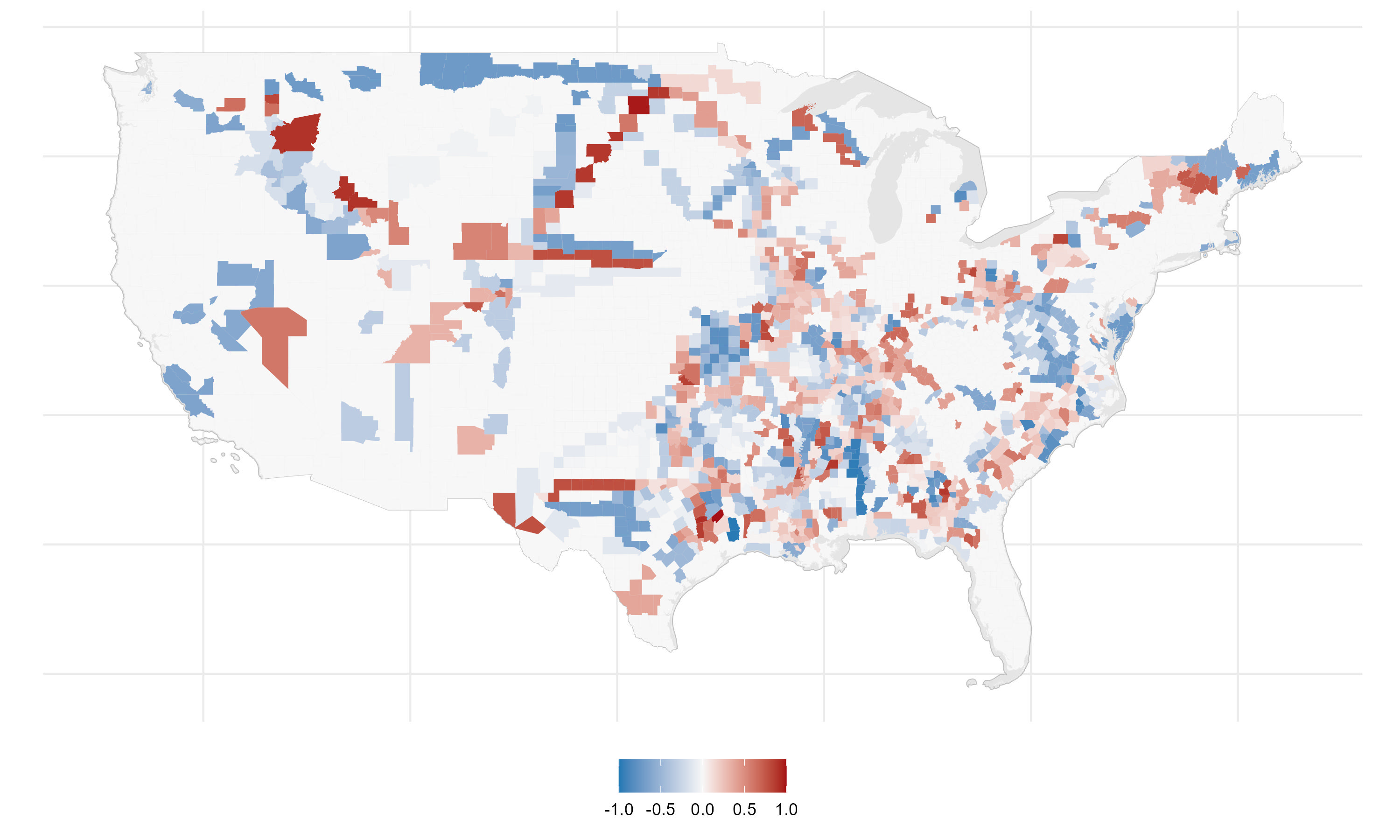

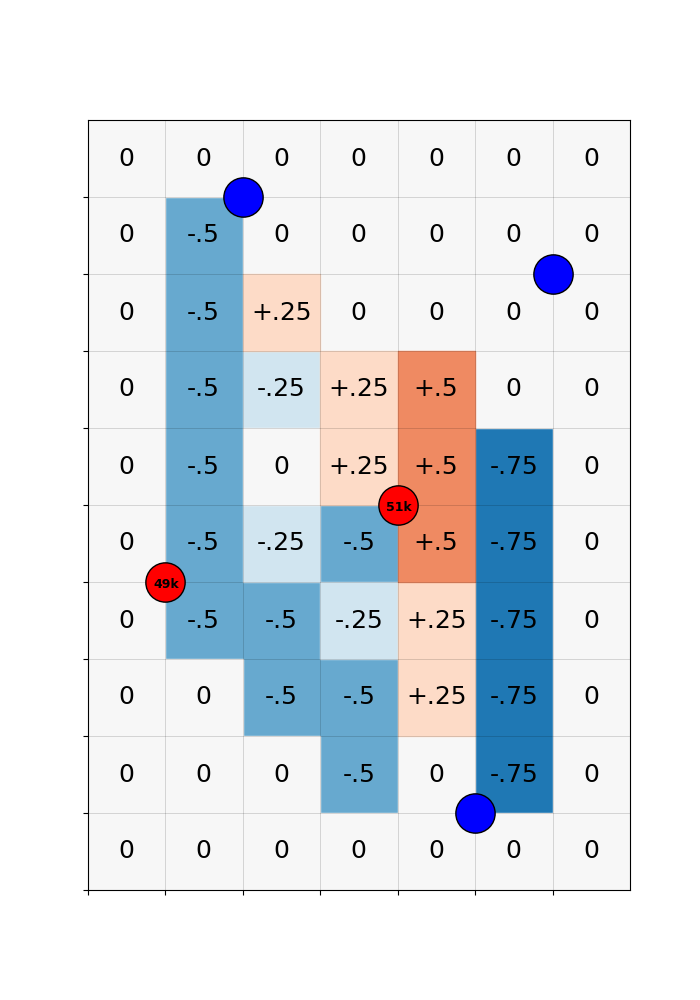

🔧 Recentered treatment captures random treatment variation

By subtracting the expected treatment from the actual treatment, we get a ‘recentered treatment’ that is purged of the systematic component. Variation in the recentered treatment is driven only by the randomness of the cutoff.

Concretely, counties with a positive recentered treatment got a highway only because they happened to be en route to a randomly included hub. Counties with a negative recentered treatment were missed, even though they could have been traversed in plausible counterfactual networks. That is good quasi-experimental identifying variation!

\[\Huge \mathbf{-}\]

\[\Huge \mathbf{=}\]

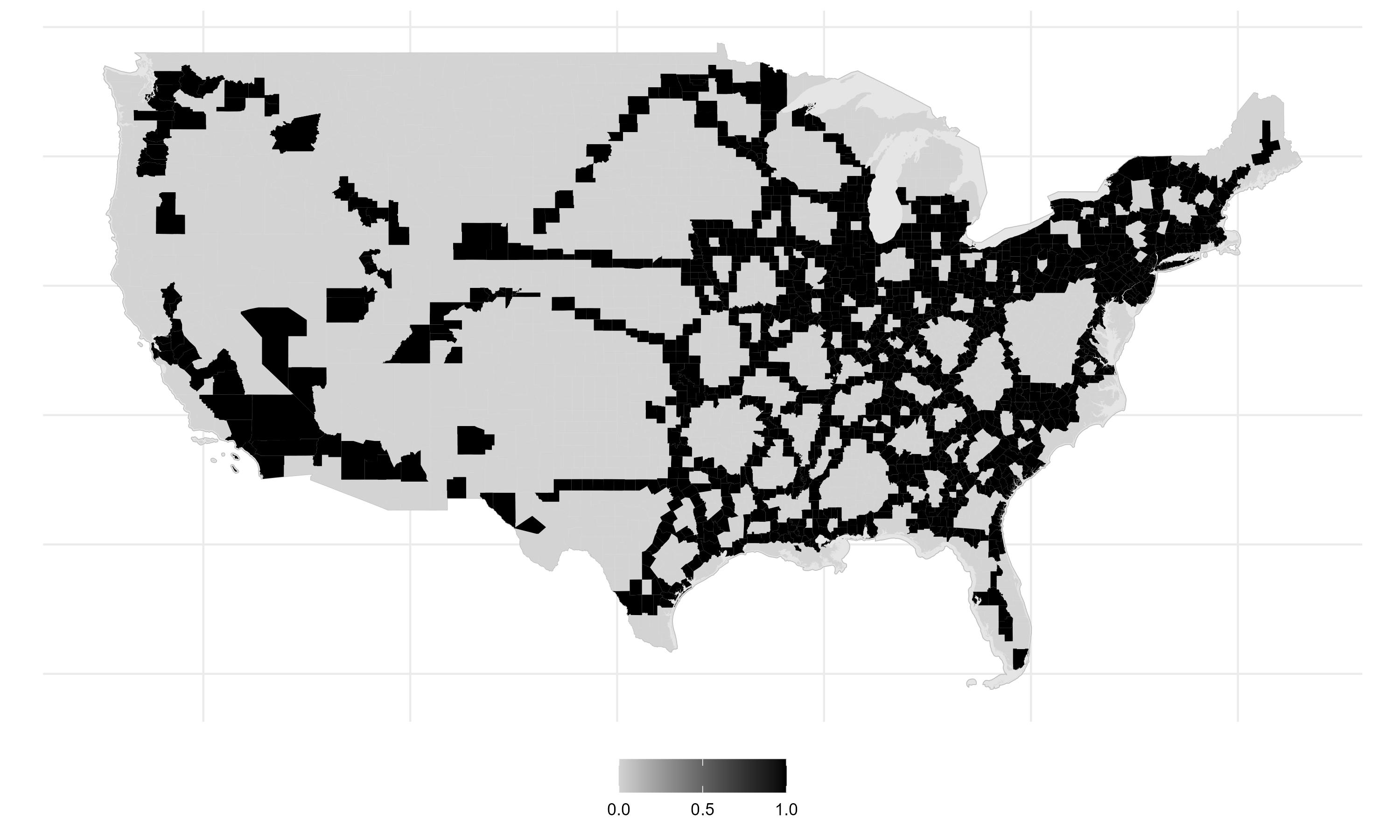

Constructing a Recentered Instrument for US Counties

Validity of Instrument

First Stage Regression

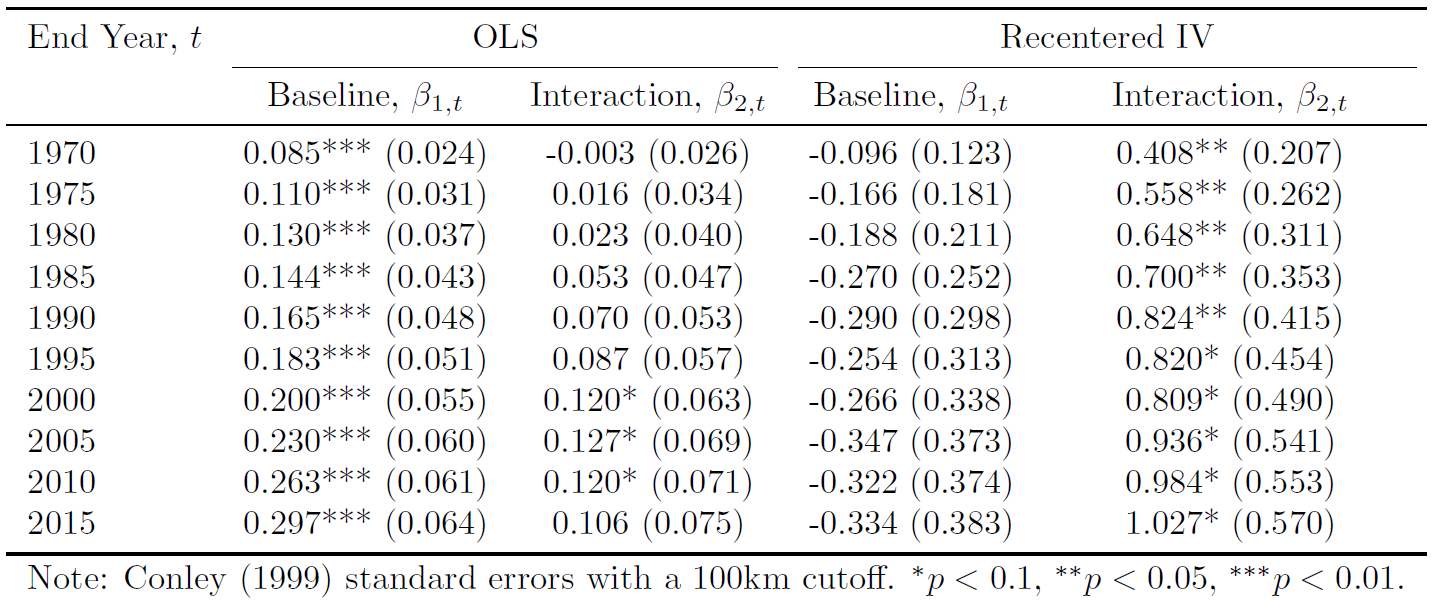

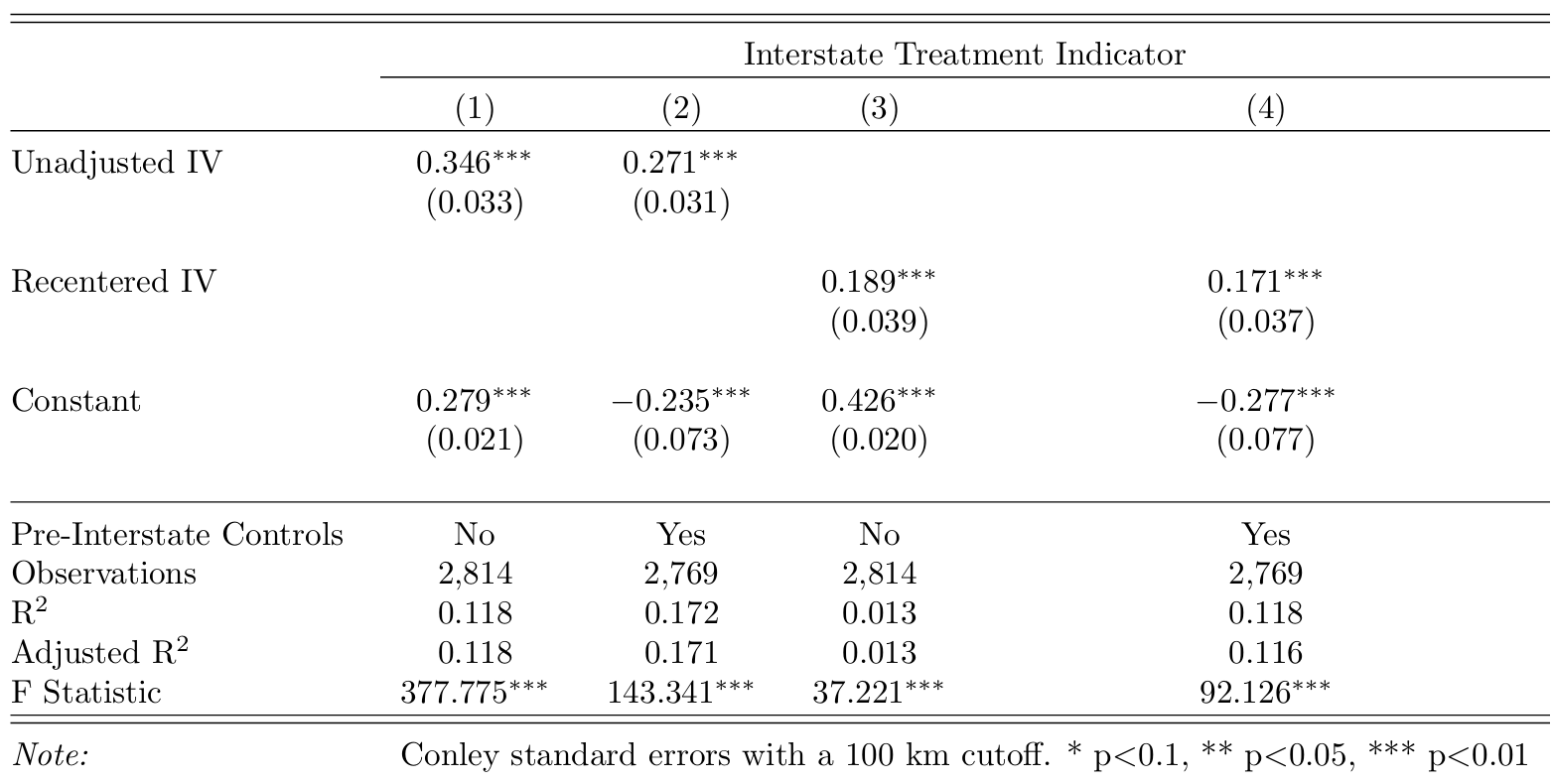

I run the following regression for \(\text{Instrument}_{c} \in \{ \text{UnadjustedIV}_{c}, \text{RecenteredIV}_{c}\}\). \[ \large \text{Treatment}_{c} = \pi_{0} + \pi_{1}\text{Instrument}_{c} + X_{c}\pi_2 + \varepsilon_{c} \]

Column (1) shows that counties with \(\text{UnadjustedIV}_{c} = 1\) are 35 percent more likely to gain Interstate access. The \(R^2\) of 0.12 indicates that the unadjusted instrument explains a meaningful share of treatment status.

Column (3) shows that counties with \(\text{RecenteredIV}_{c} = 1\) are 19 percent more likely to gain access. Focusing only on plausibly exogenous deviations explains about 1.3 percent of the variation in access, yielding an \(F\)-statistic of 37. While the predictive power is limited, this is expected in a design that strips away systematic exposure. Unlike natural experiments that rely on assumptions about counterfactual outcomes, this strategy relies on assumptions about shock assignment. The weak first stage reflects the fact that little in the actual construction process was random—a feature that, if anything, is reassuring.

Testing the exclusion restriction

To interrogate the exclusion restriction, I test for correlatedness between \(\text{RecenteredIV}_{c}\) and counties’ pre-Interstate employment growth, pre-Interstate characteristics, and latitude and longitude.

You can see these regression tables here:

IV Estimates of the Employment Growth Regression

Let’s now revisit our regression model, using the recentered instrument to instrument for \(\text{Treatment}_{c}\)

\[ \log(Y_{c, t}) - \log(Y_{c,1953}) = \beta_{0,\tau} + \beta_{1,\tau}\,\text{Treatment}_{c} + X_{c}\gamma_{\tau} + \delta_{t} + \varepsilon_{c, t} \]

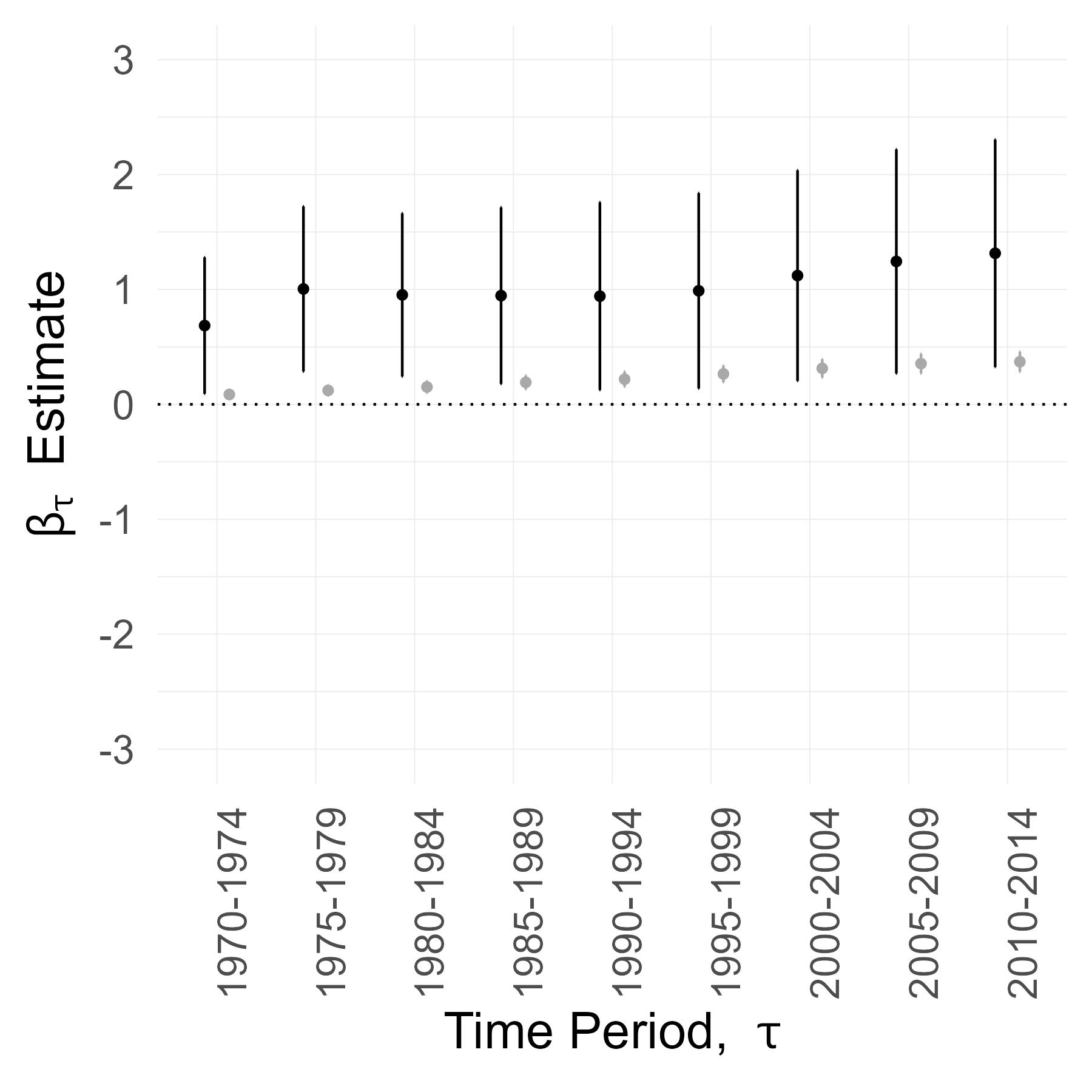

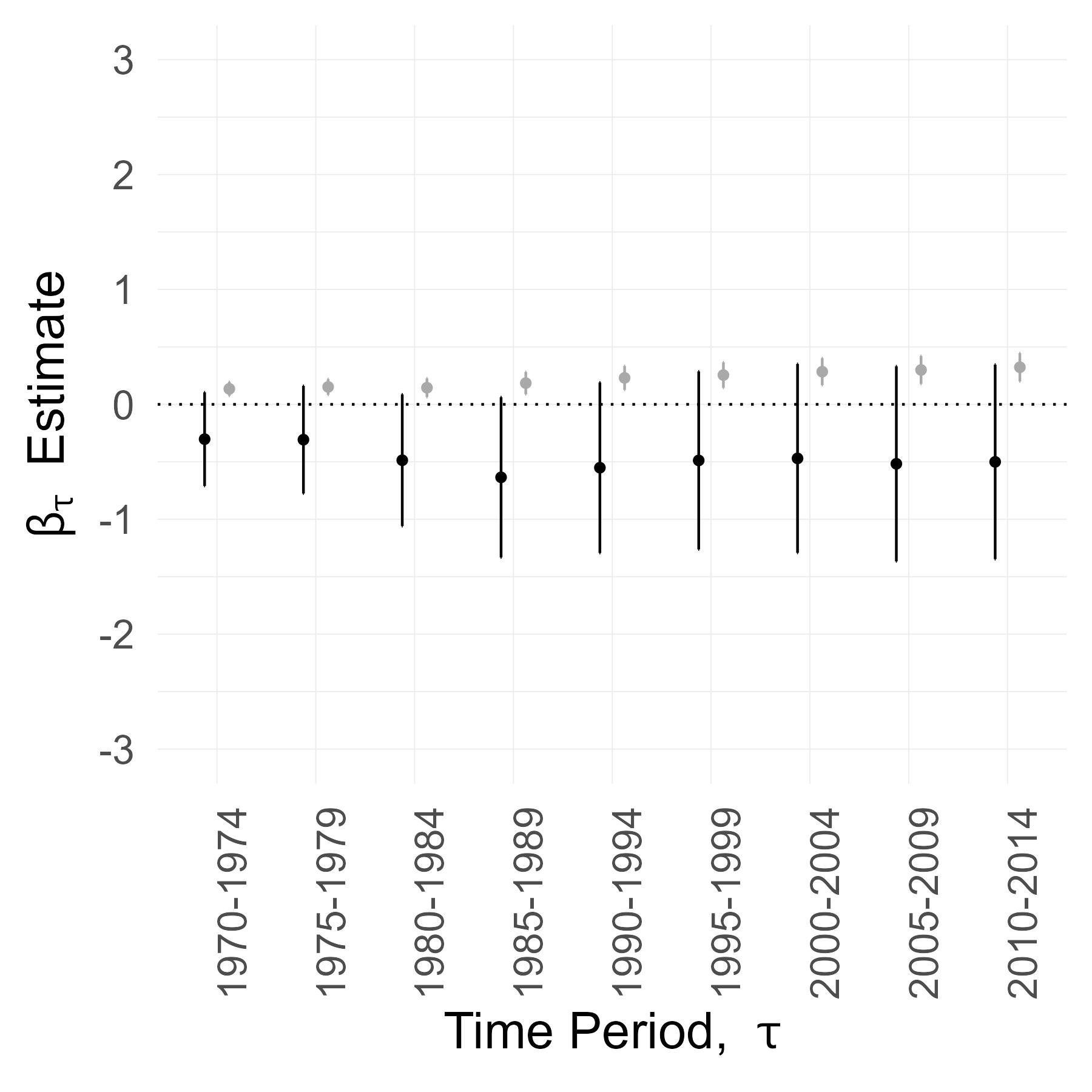

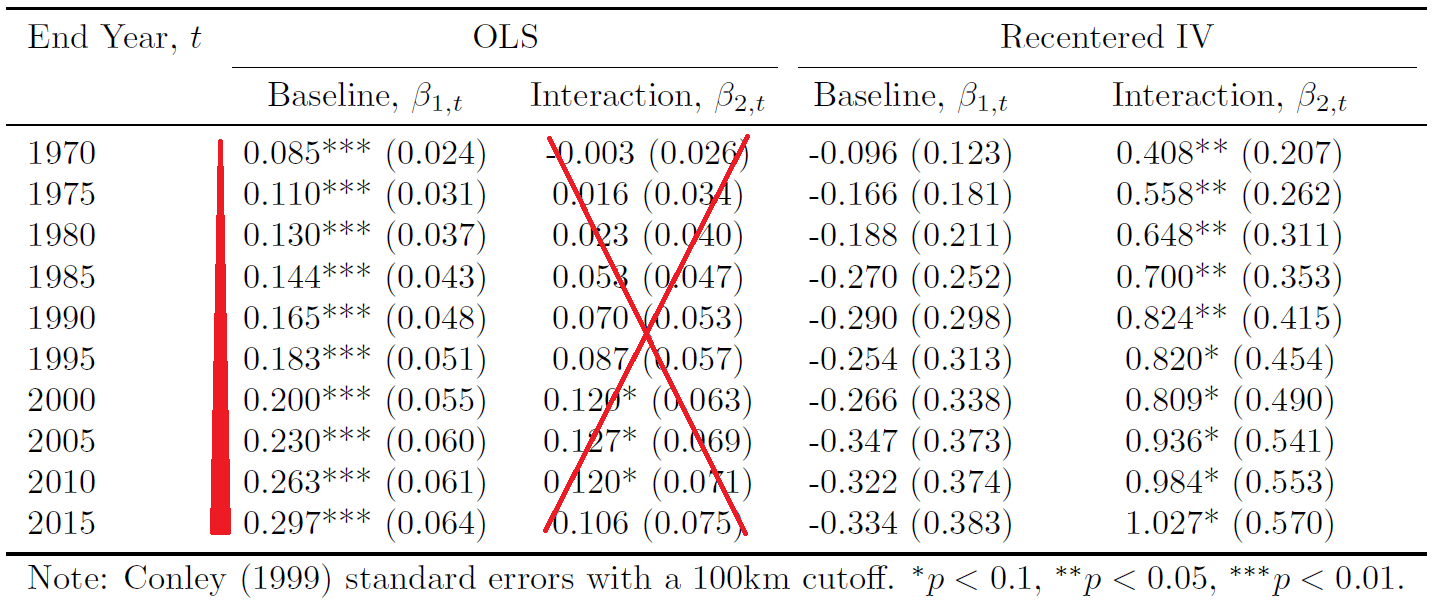

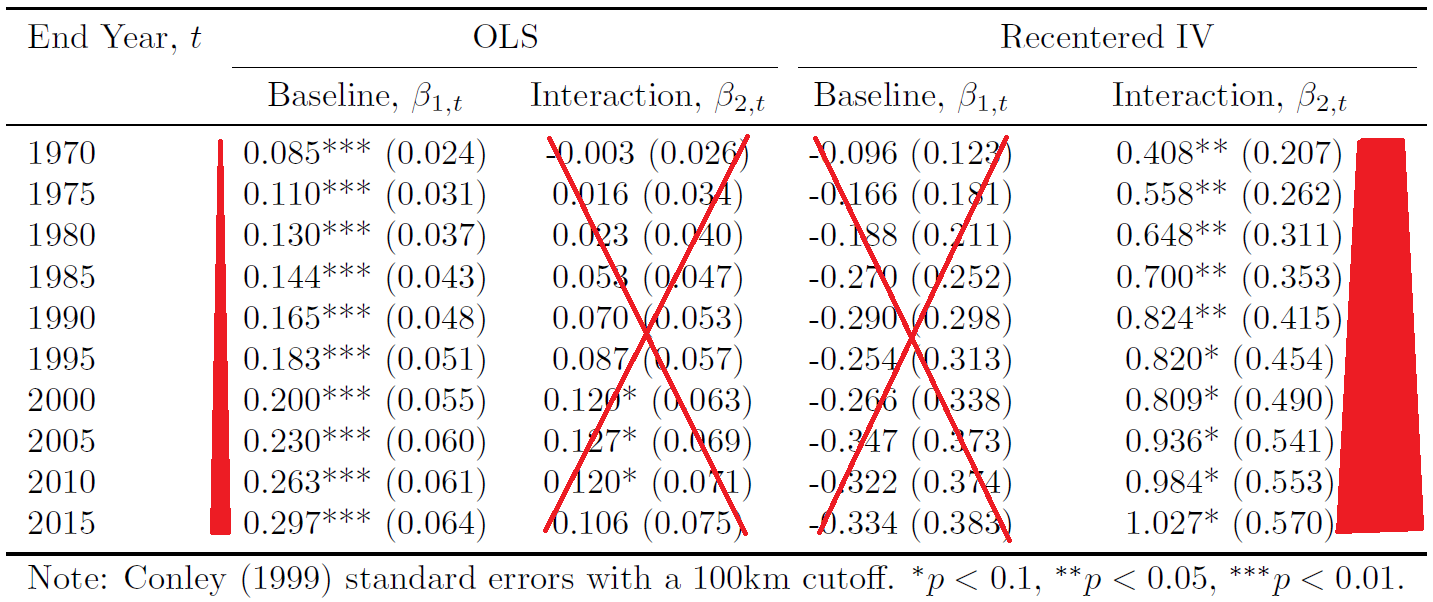

Heterogeneity Across Agriculture Dependence

Splitting the sample into high vs low agriculture groups suggested an effect heterogeneity but, to formally test for this and to more closely examine the dynamics, I set up a different regression specification.

To capture dynamic effects with total flexibility, I estimate a separate regression for each year \(t \in \{1970, ..., 2016\}\) For each year \(t\), I estimate the following specification, with counties indexed by \(c\):

\[

\log(Y_{c, t}) - \log(Y_{c,1953})

= \beta_{0,t} + \beta_{1,t}\text{Treatment}_{c} + \beta_{2,t} ( \text{Treatment}_{c} \times \text{High Ag}_{c}) + \beta_{3,t}\text{High Ag}_{c}

+ X_{c}\gamma_{t} + \varepsilon_{c, t}

\]

❔ How is this different?

This differs from fitting the previous regression separately for high- and low-agriculture groups because:

I estimate coefficients separately by year, so each regression uses N = 2,769 counties.

\(\gamma_{t}\), the weight on pre-Interstate characteristics, can now vary by year \(t\) rather than being fixed within each period \(\tau\).

The regression produces estimates and standard errors for \(\beta_{2,t}\), enabling a formal hypothesis test for heterogeneity across agriculture dependence.

To use \(\text{RecenteredIV}_{c}\), I check that the first stage is strong and that the exclusion restriction holds for the interacted instrument.

Possible explanations for this heterogeneity

One possibility is that Interstate access accelerated industrialization in counties that were initially dependent on agriculture. Alternatively, lower transport costs may have reinforced agricultural specialization rather than diversification.

I cannot find clear evidence for Interstates inducing big sectoral shifts. We would need more statistical power to identify the causal effect on sector shares. However, simple treatment–control comparisons show similar long-run declines in primary-sector employment across groups. Interstate access did not appear to accelerate the transition out of agriculture.

If Interstate access made high-agriculture counties grow larger, but not more industrial, a plausible explanation for this heterogeneity is that farm-related jobs are less mobile. Farms are more likely to remain local after transport costs fall, whereas factories or offices can relocate more easily toward denser areas.

| Treatment Counties | Control Counties | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary sector share 1950 | 0.39 (0.0052) | 0.44 (0.0037) |

| Primary sector share 1990 | 0.07 (0.0023) | 0.12 (0.0026) |

| Change in primary share 1950–1990 | -0.31 (0.0046) | -0.32 (0.0033) |

🔍 Summary

Since the system’s construction, employment has become more concentrated in counties connected to the Interstate network. On average, employment growth has been about one-third higher in counties with Interstate access than in those without.

Of course, highways were not placed at random. The Interstate system was planned to connect metropolitan areas, so this comparison reflects selection bias. These trajectories could be driven by concurrent forces of urbanization rather than by Interstate access itself.

From Interstate planning documents, I discover an overlooked natural experiment and discern that many counties were non-randomly exposed to this exogenous shock to Interstate access. Adapting Borusyak & Hull’s (2023) recentered instrument framework, I use predicted counterfactual networks to isolate quasi-experimental variation from this planning shock.

I find that, among counties between major population hubs that as-good-as-randomly gained access, Interstates increased employment only where agriculture was initially important.

Hello - thank you for visiting this site!

My name is Charoo Anand and I’m a PhD candidate at Berkeley Econ, on the job market for data scientist/economist roles.

You can reach me at charoo_anand [at] berkeley.edu or on LinkedIn.